July 31, 2015

Japan's Depopulating Society: Population Concentration in Tokyo and the Disappearance of Local Municipalities (Part 2)

Keywords: Aging Society Newsletter Population Decline Steady-State Economy

JFS Newsletter No.155 (July 2015)

Image by John Gillespie Some Rights Reserved.

The previous issue of the JFS Newsletter introduced problems resulting from a declining population and future challenges for Japan nationwide. It was based on the first half of an April 23, 2015, lecture on the depopulation in Japan, by Hiroya Masuda, who is chairperson of the private think tank Japan Policy Council (JPC) and guest professor at the Graduate School of Public Policy of the University of Tokyo.

This issue of the JFS Newsletter continues with the second half of Masuda's lecture, focusing on Tokyo's challenges, which are aggravating the situation in Japan, and possible solutions for smaller municipalities away from the metropolis.

Excess Concentration of Population in Tokyo:

Young People Continue Moving In from Around the Country

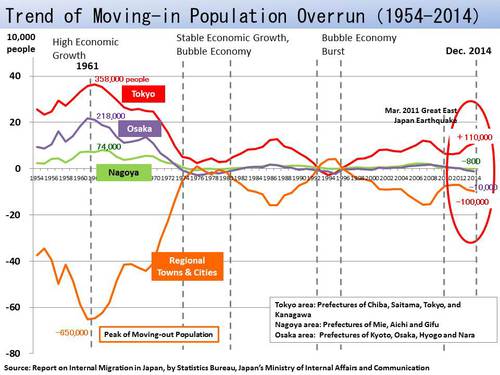

The trend of population flow in Japan since the period of high economic growth in the 1960s reveals an over-concentration of people in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Data on changes-in-residents' registration in 1961 show that areas away from the big cities faced a decline in population of 650,000, while three large cities had a considerable inflow of people (about 360,000 into the Tokyo area, 220,000 into the Osaka area, and 70,000 into the Nagoya area).

Since that time, however, the population has been growing only in the Tokyo area and not Osaka or Nagoya. Statistics for 2014 show that 100,000 people moved out of regional towns and cities, while 110,000 people moved to Tokyo. Since the population itself is declining in Japan, the overall number moving in is decreasing, but it is apparent that a majority of people moving from the regions are coming to Tokyo.

Data from residents' registries shows that the largest age group moving to the Tokyo area is 20- to 24-year-olds, the age when most people enter the job-seeking phase, followed by newly enrolled students at universities and colleges in Tokyo. Ninety-five percent of the 110,000 people who moved to Tokyo in 2014 were of the younger generation, people of a child-bearing age.

Tokyo Area Seeing Low Birth Rate and Increasing Number of Seniors

Despite the inflow of young people, the total fertility rate (TFR) in Tokyo was 1.13 in 2013, very low compared to the national average of 1.43. (TFR is the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime.) A TFR of 1.13 basically means that most couples have only one child. As a result, the number of children is dropping in Tokyo, creating an inverted V in the population curve. It is a big problem for the overall Japanese population that a large number of young people are moving to Tokyo, where the birth rate is low.

The Tokyo metropolitan area will also see an explosive increase in the number of elderly people at the same time birthrates are dwindling. Outside the metropolis, on the other hand, there is a concern that many municipalities are at risk of disappearing entirely due to population decline, but it is actually Tokyo that will have to face a more difficult situation than any other municipality.

The post-war baby boom generation in Japan will reach the age of 75 or older in 2025, bringing with them a pressing need for medical and nursing care. Even today, in Tokyo, many seniors are on waiting lists for "special elderly nursing homes," or public nursing-care facilities run by municipalities or social welfare corporations (the number of names on the lists often exceeds 1,000 per facility), making it extremely difficult for older adults to move in to the special elderly nursing homes in any of Tokyo's 23 wards. Such facilities on the outskirts of Tokyo also have little room to accept new applicants. Thus, in some cases, seniors in need of nursing care have to find a care home located away from Tokyo.

Caring for the elderly at home, on the other hand, requires constant care and attention. Because of this, an increasing number of people are forced to give up their jobs. In Tokyo, people seem to have better access to medical services, but the situation will deteriorate in light of estimates that the senior population will more than double. In large hospitals, for example, patients will have to wait for three to four hours just to have a 10-minite examination. Such cases are expected to occur more often.

Regional Towns and Cities Can Address Elderly Issues More Easily

The number of elderly people in regional towns and cities is projected to decrease by 2040, which will allow local hospitals and nursing-care facilities to have more capacity to operate.

At the same time, however, these municipalities will have to face economic difficulties. According to an estimate made about a decade ago, revenue sources for a typical municipality with a population of about 10,000 in semi-mountainous areas were from seniors' pensions, public works, and profits from agriculture, forestry, commerce, and industry, each of which accounts for one-third of the total. Pensions are paid to the elderly every two months and used for shopping and other costs, but the number of elderly people will decrease, leading to less revenue. In addition, public works are on a sharp decline. Thus, the revenues of these municipalities will shrink.

Under these circumstances, regional towns and cities should create more job opportunities, for instance, in the agriculture sector. Previously, the total fertility rates in agricultural areas were very high, but now, the rate is 1.4 in Iwate Prefecture and 1.28 in Hokkaido Prefecture, for example. To increase the number of children in these areas, work environments in the agricultural sector must be improved so that young women may be more willing to engage in agriculture. Otherwise, it will be difficult for many agriculture-based municipalities to sustain their population levels.

A good example is the case of the village of Ogata, Akita Prefecture, where agricultural corporations have large-scale mechanized farming operations, using machines for farm work that would otherwise be strenuous even for male workers. Farming done by companies also involves desk work such as bookkeeping, which women can also do.

An example in the service industry is tourism in the town of Niseko, Hokkaido Prefecture, where the number of tourists from overseas countries, including Australia, has been increasing. More interpreters are needed and hotel receptionists are required to speak English, which means Niseko has more jobs for women than before.

In Tokyo, for economic reasons (high costs), young workers in their twenties or thirties often cannot live near their workplaces, so they spend an average of more than three hours commuting to and from work. In addition they often have to put in a lot of overtime work hours, which exhausts them. These conditions also keep young people from getting married or having children.

Komatsu Ltd. is a positive example of how some companies are addressing these problems. This multinational manufacturer, which has its head office in Tokyo, moved its human resources training base to the city of Komatsu, along the Sea of Japan, in Ishikawa Prefecture. According to an in-house survey, female managers working in Komatsu had three children on average, while those in Tokyo had only 0.9. With just 30 minutes of commuting to the office, workers in Komatsu can go home when needed and then return to their workplace. In contrast, workers in Tokyo who need one-and-a-half hours one way cannot get home quickly, even when something urgent happens. In this regard, life is better for working women who live outside rather than inside the major metropolises.

Like Komatsu did, other companies could relocate departments that do not have to be located in Tokyo, to areas where land prices are more reasonable, while leaving their head offices in Tokyo. If companies were to recruit workers and offer the same conditions as can be had in Tokyo, they could hire well-qualified school graduates who live in the regional towns and cities, which can be a big benefit for the company.

Along with such efforts, it will be important to make workplaces in outside the metropolises more comfortable for young workers by reducing weekend work, and other measures.

(End of Masuda's lecture)

From the editors: It is a critical structural problem that young people, whose population numbers are declining in Japan, are concentrating in Tokyo, where the birth rate is lower. Hearing that more municipalities around the country could vanish due to population decline, one might assume that they face tougher challenges, but in his lecture, Masuda showed how regional cities and towns can address the problems more easily than the big urban centers. That idea was very impressive.

Japan is facing a declining population nationwide, so the issues should be tackled by the whole nation. Solutions will come not by just thinking about things one city at a time, but by taking a wholistic and comprehensive view of the challenges.

Edited by Junko Edahiro and Naoko Niitsu

Related

"JFS Newsletter"

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.4): 'Eightfold Satisfaction' Management for Everyone's Happiness

- "Nai-Mono-Wa-Nai": Ama Town's Concept of Sufficiency and Message to the World

- 'Yumekaze' Wind Turbine Project Connects Metro Consumers and Regional Producers: Seikatsu Club Consumers' Co-operative

- Shaping Japan's Energy toward 2050 Participating in the Round Table for Studying Energy Situations

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.3): Seeking Ways to Develop Societal Contribution along with Core Businesses