September 9, 2014

Update on Japan's Efforts to Build National Resilience to Disasters

Keywords: Newsletter Resilience

JFS Newsletter No.144 (August 2014)

Building National Resilience | Cabinet Secretariat

http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kokudo_kyoujinka/index_en.html

Source: National Resilience Promotion Office, the Cabinet Office

Japan's National Resilience Promotion Headquarters, with the Prime Minister as Director General, was established based on the Basic Act for National Resilience Contributing to Preventing and Mitigating Disasters for Developing Resilience in the Lives of the Citizenry (abbreviated as Basic Act for National Resilience), enacted in December 2013. Here is a summary of an interview with an officer from the Cabinet Office's National Resilience Promotion Office, which is engaged in practical operations as secretariat.

---------------------------------------

Background

Japan has experienced many large-scale disasters. For instance, the Ise Bay Typhoon in 1959 resulted in as many as 5,098 persons killed or missing. This disaster triggered the establishment of the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act, the real beginning of present-day disaster-related measures in Japan.

Ise Bay Typhoon in 1959

Photo by Disaster Prevention Research Institute at Kyoto University Some Rights Reserved.

In the 1995 Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake, an inland earthquake with a seismic intensity at the top of the Japanese scale of zero to seven directly hit a metropolitan city, resulting in about 80 percent of the total number of casualties dying due to collapsing houses. Breakouts of large-scale fires spreading through densely-populated urban areas and the collapse of an elevated expressway also caused tremendous human losses and property damage. Learning from this disaster, the Japanese government started to upgrade quake resistance of infrastructure as well as enhance the measures to make houses and buildings more quake resistant, and measures for crowded city blocks of wooden houses. The government has strengthened design and other relevant standards after every large-scale disaster, focusing on infrastructural measures, but it has taken action mostly after disasters actually occurred.

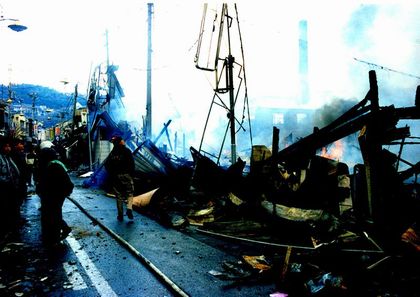

Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake in 1995

Photo by Akiyoshi Matsuoka Some Rights Reserved.

The Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011 involved a massive quake with a magnitude of nine, the most powerful on record, a huge tsunami with a maximum height of over 40 meters. Coastal levees were effective in delaying the tsunami reaching shore, but not effective enough to prevent it from hitting affected areas, resulting in a major disaster with a large number of deaths and missing persons. This disaster indirectly caused other serious problems, such as disruptions when many commuters were unable to go home in the Tokyo metropolitan area, and shortages of gasoline. On the other hand, in some cases many lives were saved thanks to evacuation actions based on disaster prevention education conducted on a regular basis. One is known as the "Miracle of Kamaishi," in which students of a primary and secondary school in the city of Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture, avoided becoming tsunami victims by running uphill toward a designated evacuation area immediately after the big quake occurred, just as they had been instructed to do and had practiced in disaster drills.

Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011

Photo by ChiefHira Some Rights Reserved.

The 'Miracle of Kamaishi': How 3,000 Students Survived March 11

http://www.japanfs.org/en/news/archives/news_id034287.html

One of the lessons learned from the Great East Japan Earthquake is that there are limits to disaster-related measures that focus on upgrading individual infrastructure components based on the idea of "protection." It is necessary to enhance the strength, flexibility, and overall resilience of society and the economy by combining both infrastructural and behavioral or institutional (i.e., hard and soft) measures.

History

After the Great East Japan Earthquake, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party established the National Resilience Investigation Committee, which conducted two years of discussions on how the government should build national resilience. In December 2012, when the second Abe Cabinet was formed, the position of Minister in Charge of National Resilience was created in the Cabinet to address the issue of building national resilience, one of the Cabinet's top priorities. In January 2013, the National Resilience Promotion Office was established in the Cabinet Office as secretariat to spearhead the discussions, and in December that same year, a members' bill was enacted as the Basic Act for National Resilience.

What are the Differences between "National Resilience" and "Disaster Prevention"?

Disaster prevention focuses mainly on emergency response, meaning "What we should do after a disaster occurs." Response manuals are organized under categories such as "When an earthquake occurs" and "When a nuclear disaster occurs." On the other hand, the conventional disaster prevention efforts themselves have not necessarily been enough when considering how we can protect our lives and mitigate damages in ordinary times, and the government should reflect on that.

A clear example of this was the tsunami caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake. The tsunami collapsed breakwaters in Kamaishi, sweeping away and killing many people who assumed that it would not reach them. If they had been instructed to "run away" like the students described in the "Miracle of Kamaishi," more might have survived. Structural measures are important, of course, but non-structural measures are more important. In the national resilience policy, both structural and non-structural measures are regarded as important. This is the difference from traditional disaster prevention measures. It is forecast that great earthquakes, including ones occurring directly beneath the Tokyo Metropolitan Area and Nankai megathrust earthquakes, will occur in Japan in the future. It is necessary to enhance capabilities to deal with these disasters in advance.

How to Build National Resilience

The following four "Fundamental Goals for National Resilience" were established by meetings of the Advisory Committee on National Resilience (Disaster Reduction and Mitigation) held since February 2013:

- Ensure the protection of human lives to the extent possible.

- Avoid fatal damage to important functions of the nation and society and ensure that such functions are maintained. (The word "functions" shows the fact that the targets to be protected are not limited to physical facilities and infrastructure.)

- Minimize damage to the property of the citizenry and public facilities.

- Contribute to swift recovery and reconstruction.

According to these four goals, the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle shown below is followed and reviewed repeatedly to promote national resilience.

(1) Identify and analyze risks

(2) Identify vulnerabilities

(3) Assess vulnerabilities and consider remedial measures

(4) Prioritize and implement the remedial measures

(5) Evaluate the results

Expert meetings of the Advisory Committee on National Resilience (Disaster Reduction and Mitigation) identified 45 worst-case scenarios that should be avoided, termed "situations that should never happen." Traditionally, measures were taken against hazards such as "earthquakes" and "storm and flood damages." This plan, however, starts with an emphasis on the risks of certain impacts, regardless of the type of hazard that causes them. Natural disasters are regarded as the primary hazards posing risks.

Below are the top 15 "situations that should never happen," selected for priority measures.

- Casualties due to large-scale collapse of multiple buildings and transportation facilities in urban areas, or fires in densely-populated residential areas

- Extensive loss of life over a large area due to a large tsunami, etc.

- Prolonged and wide-area flooding in urban areas due to abnormal weather, etc.

- A large number of casualties due to a large volcanic eruption or sediment disaster (deep-seated slope failure), etc., which may also increase vulnerability of national land over years to come

- A large number of casualties due to delay in evacuation caused by failure of information transmission, etc.

- Prolonged suspension of supply of food, drinking water, and other vital goods

- Absolute lack of rescue and emergency activities due to damage to the Self-Defense Forces, the police, fire services, Japan Coast Guard, etc.

- Failure of central government functions in the capital region

- Paralysis and prolonged suspension of information transmission due to suspension of power supply, etc.

- Loss of international competitiveness due to a decline in companies' productivity caused by disruption of supply chains, etc.

- Suspension of energy supply necessary for social economic activities and the maintenance of supply chains

- Dysfunction of the core road/marine transport networks, such as disruption of transportation arteries in the Pacific belt zone

- Obstructions to the stable supply of food, etc.

- Suspension of functions of power supply networks (power generating/transforming stations, transmission/distribution equipment) and oil/LP gas supply chains

- Expansion of damage due to devastation of farmland and forests

See also:

http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kokudo_kyoujinka/pdf/shishin1-1.pdf

At the National Resilience Promotion Office, we created a big 45-by-12 matrix with 45 of the worst-case situations that should never happen in rows and 12 individual sectors of measures in columns, in order to facilitate vulnerability assessment. In the table, we filled in measures that have already been conducted by governments in the sectors of "administrative functions," "housing and cities," "information and telecommunications," etc., for each of the 45 scenarios. Using this table, we identified which measures are non-existent or insufficient for each scenario.

In the first vulnerability assessment, we identified whether or not there were measures to address each of the scenarios. After that, we conducted a more elaborate assessment with indicators showing the progress of each measure, with a view to establishing the Fundamental Plan for National Resilience. For example, the future goal regarding "houses and fire in the event of earthquake" is that 95 percent of residential houses nationwide will be resistant to quakes by fiscal 2020. We evaluated current progress toward the goal and considered what will be necessary to attain it.

Image by Haruhiko Okumura Some Rights Reserved.

The United Kingdom and the United States are also undertaking efforts based on their own national resilience plans, but we think the way of determining "situations that should never happen" to assess the vulnerability is unique to Japan.

We will incorporate concrete steps into the Fundamental Plan to address weaknesses identified by the vulnerability assessment for the 12 sectors of measures. For instance, measures for "police and fire services" include the reinforcement of: the police system necessary for emergency life-saving activities; emergency response units in fire fighting; the Technical Emergency Control Force (TEC-FORCE) that visits disaster-stricken areas to investigate the status of damage and formulate necessary measures; and human resources. Also, cross-cutting sectors consist of risk communication, countermeasures for aging infrastructure and research and development. We will draw up a five-year fundamental plan and an action plan for the 45 programs, and will review them every year.

The Fundamental Plan for National Resilience is called the "umbrella plan," under which are the Basic Disaster Prevention Plan and the National Land Formation Plan. Further below them are the plans of relevant ministries and agencies, such as the Basic Energy Plan, the Basic Plan on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas, and the Social Capital Development Plan. This means that the Fundamental Plan for National Resilience is designed to reflect cross-sectional plans, such as the Basic Disaster Prevention Plan and the National Land Formation Plan, as well as on plans of each individual sector which exist underneath the cross-sectional plans.

The Basic Act for National Resilience also specifies the development of regional plans. The Act says that each local government (prefectures, cities, towns, and villages) can develop its own plans to improve resilience. In order to support local governments on this matter, the national government has prepared guidelines for formulating regional plans, and also plans to dispatch experts to several regions as model studies, where they will give local governments advice on the establishment of regional plans.

Image by Rikujojieitai Boueisho Some Rights Reserved.

The United Nations World Conference for Disaster Risk Reduction, held every ten years, will be held in 2015 in the city of Sendai, one of the areas stricken by the 2011 quake and tsunami in Japan. One of this conference's themes is "resilience," so we hope to use it as a venue to exchange information on national resilience with participants from abroad and to build a network with them.

UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction

---------------------------------------

Leading up to the 2015 conference, Japan for Sustainability will also communicate views of resilience from various perspectives and relevant efforts from Japan. Stay tuned!

Written by Junko Edahiro

Related

"JFS Newsletter"

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.4): 'Eightfold Satisfaction' Management for Everyone's Happiness

- "Nai-Mono-Wa-Nai": Ama Town's Concept of Sufficiency and Message to the World

- 'Yumekaze' Wind Turbine Project Connects Metro Consumers and Regional Producers: Seikatsu Club Consumers' Co-operative

- Shaping Japan's Energy toward 2050 Participating in the Round Table for Studying Energy Situations

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.3): Seeking Ways to Develop Societal Contribution along with Core Businesses