April 21, 2016

Kodomo-Shokudo Project to Provide Children with a Warm Meal and Place to Visit

Keywords: Food Newsletter Well-Being

JFS Newsletter No.163 (March 2016)

There are many initiatives providing food to people in need in both developing and developed countries. For example, the Food Bank project has become popular mainly in the United States and Europe to provide food that would have been discarded to facilities and people needing food. In Japan, regional food bank networks are also being built. One recent initiative in Japan has been Kodomo-Shokudo (children's cafeteria). What is Kodomo-Shokudo? In this issue of the JFS Newsletter, we feature this grass-roots initiative, describing its background in Japan.

One in Six Children in Japan Impoverished under Widening Economic Disparity

According to the 2012 Annual Report on Health, Labor and Welfare, the relative poverty rate* of children under 18 was 16.3 percent, meaning an alarming one in six children were in poverty in Japan.

* The term "relative poverty rate" is frequently used to describe poverty in developed countries. It is the proportion of people with income below half of the median equivalent income ("Median" means the middle number when arranging a set of numbers in value order). By contrast, the "absolute poverty rate" is used as an index to express poverty in developing countries, and is the proportion of people whose income or expenses are below a certain level. For example, the World Bank defined the absolute poverty rate in 2008 as the proportion of people with living expenses of less than U.S.$1.25 per day.

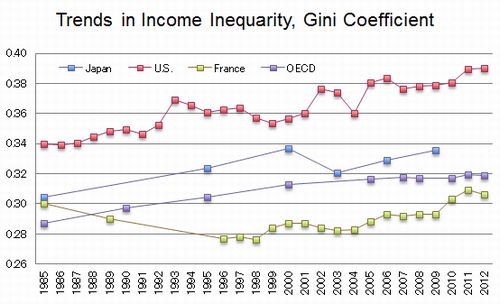

Japan has long been regarded as a country with low economic disparity. This is symbolized in the phrase "a hundred million people, all middle class" that became popular in the 1970s. The Gini coefficient*, representing inequality and disparity, was small around 1970 in Japan, indicating low disparity in income, but then gradually increased to today's level, which is well above the OECD average. In other words, Japan has a wider economic gap than the average OECD country.

Source: OECD In It Together, in Japan

*The Gini coefficient is an index representing the degree of social disparity in income. Gini coefficients range between 0 and 1. Values nearer to 0 represent less disparity and those nearer to 1, greater disparity.

With greater economic disparity, poverty has become a serious problem. According to OECD Fact Book 2010, Japan's relative poverty rate is the fourth highest among OECD member countries. Especially serious is poverty among single-mother families. Data for 2011 show the average income of families with children to have been 6.97 million yen (about U.S.$58,000) while that of single-mother families was 2.91 million yen (about U.S.$24,300), including allowances, according to the Nationwide Survey on Fatherless Families by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Poverty among children has become a social concern.

Approaches to Child Poverty

Poor children have insufficient educational opportunities due to difficult life circumstances. This may result in long-term influences such as widened disparities in future income. The Japanese Government enforced the Act to Accelerate Measures for Disadvantaged Kids in 2015 to support poor children's education, life circumstances and employment, but governmental efforts are still insufficient.

Concerning child poverty, the problem of food is also serious. Some students have supper alone, eating snacks or convenience store box lunches, because their parents have to work even at suppertime. Most such children obtain nutrition only from school lunches, and teachers say some students lose weight after long school holidays such as summer vacation. Some seriously poor families cannot afford school lunch fees.

One grass-roots approach to solving such food problems among poor children is Kodomo-Shokudo.

What is Kodomo-Shokudo?

Kodomo-Shokudo provides free or reduced-price meals to children. Differing from ordinary restaurants that operate almost every day, most of them open once or twice a month, managed by volunteer staff. Most ingredients are supplied through donations. Users of Kodomo-Shokudo include children from families in economically difficult situations or with little time to prepare meals because of both parents having to work.

For instance, there is a Kodomo-Shokudo that opens from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. on the first and third Wednesday each month, and anyone can eat dinner there for 300 yen (U.S.$2.50). Another cafeteria opens from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. every Monday offering meals for free to children and for 300 yen to adults.

Kodomo-Shokudo has drawn rapidly increasing attention in the last couple of years, and we often see newspaper articles reporting a children's cafeteria opening in one area or another. There are also many people who would like to open their own. In fact, the second Kodomo-Shokudo Summit, held in January 2016 reached its admission capacity of 200 people beforehand, attracting strong interest.

Various Types of Kodomo-Shokudo

We call these programs "Kodomo-Shokudo" in short, but each of them is unique and has various roles in addition to just providing meals. For example, many programs provide a place for children to study or play before and after meals. Some programs with a focus on providing "space" try to attract a variety of people regardless of age and nationality, without using the name "Kodomo-Shokudo." In such cases, parents participating in programs with their children can find someone to talk to regarding their worries about parenting.

Kodomo-Shokudo programs are conducted in various venues, including shops, residential homes and temples. Residential homes may have difficulties preparing meals because of insufficient cooking facilities and lack of large pots. In this regard, temples may be more suitable for programs. Temples usually have a large kitchen equipped with large pots and many dishes. In addition, temples have plenty of space for children to play.

In one unique example, retired men play a major role in cooking meals for a Kodomo-Shokudo. A newly coined term "ikumen" (men who actively participate in child-rearing) is often heard these days, and "ikumen" are no longer rare. Many Japanese men, however, are too busy with work in their younger years to make time for active involvement in child-rearing and community activities. Through the operation of Kodomo-Shokudo, these men can connect with children and other people in the community.

A Kodomo-Shokudo at a house owned by an elderly person can provide children with a chance to interact with seniors. In other programs, children are encouraged to help prepare meals so that they can learn how to cook meals for themselves.

Therefore, Kodomo-Shokudo programs have the potential to address various issues in communities and society. Little by little, municipalities have been moving toward providing support for Kodomo-Shokudo in recent years.

Difficulties in Operating Kodomo-Shokudo

Kodomo-Shokudo programs are now spreading, but there have been some difficulties in getting the programs on track. The largest challenge is that it takes time before children in need come to Kodomo-Shokudo. People involved in the programs say that the number of children participating is often small at the beginning. In some cases, adult volunteers and visitors outnumber the children, joking that it is a cafeteria for adults rather than kids. They also say, though, that the number of children gradually increases through word of mouth and social networking services (SNS), as they continue opening Kodomo-Shokudo on a regular basis.

Are there any grass-roots initiatives addressing food issues associated with child poverty in your area? If there are any, please share them with us.

Written by Naoko Niitsu

Related

"JFS Newsletter"

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.4): 'Eightfold Satisfaction' Management for Everyone's Happiness

- "Nai-Mono-Wa-Nai": Ama Town's Concept of Sufficiency and Message to the World

- 'Yumekaze' Wind Turbine Project Connects Metro Consumers and Regional Producers: Seikatsu Club Consumers' Co-operative

- Shaping Japan's Energy toward 2050 Participating in the Round Table for Studying Energy Situations

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.3): Seeking Ways to Develop Societal Contribution along with Core Businesses