February 28, 2017

Toward a Sustainable Society - Learning from Japan's Edo Period and Contributing from Asia to the World

Keywords: Ecosystems / Biodiversity Newsletter Policy / Systems Steady-State Economy Well-Being

JFS Newsletter No.174 (February 2017)

Image by EntretenimientoIV.

Junko Edahiro, chief executive of Japan for Sustainability, delivered a keynote speech on February 21, 2017, at the second Asia-Pacific Region System Dynamics Conference of the System Dynamics Society, held in Singapore. This month's JFS newsletter will introduce her speech, titled "Toward a Sustainable Society - Learning from Japan's Edo Period and Contributing from Asia to the World."

https://apconference.systemdynamics.org/

Greeting

I am very honored to have been invited to speak here, and would like to express my appreciation to the Organizing Chair, John Richardson, and to everyone involved in this conference.

Many of you at the System Dynamics Society probably know the Balaton Group. It is a global network of experts and practitioners of system dynamics, systems thinking, and sustainability -- established by Dennis Meadows and Donella Meadows. In September 2002, I was one of the recipients of the first Donella Meadows Fellowship, and participated in the Balaton Group annual meeting for my first time. At that time, John was there, participating for his second time in 20 years.

We hit it off right away, and since then, with every Balaton Group meeting, have been talking about many things. I am writing a book entitled "Making Life Peak in Your Nineties," and for that John has kindly shared a lot of knowledge and inspiration with me.

You may think, "Wait a minute! How can a person's life peak in the nineties?" I too used to have the impression that the highest point of one's life was retirement age in the sixties or earlier, followed by a steady decline. But now it is gradually rising and I am aiming for the nineties.

You may know that in Japan already 1 in 4 people is 65 or older, and I think the happiness and contributions of the elderly in Japan are expected to rise People often tell me, "A person's life peaking in the 90s? I'm surprised!" Yes, I like to surprise people.

Sustainability?

The title of my talk today is "Toward a Sustainable Society." Don't you think the title itself is a bit strange? If we talk about moving "toward" a sustainable society, that implies that we think it is NOT a sustainable society today. Why are we witnessing a series of growing environmental problems, like climate change and biodiversity loss? Let's talk about that.

Above all, there is only one Earth, and over the few billion years since its formation, it has not grown in size. That is a basic fact. And in principle, the Earth is more or less a closed system. Solar energy from the sun is the only thing coming into the Earth, and only thermal radiation is released into space. If rain falls, a child might imagine new water is coming from space, but actually, we have a closed system on the Earth and water is only changing its state as it circulates. New water and material is not coming from space, and none of it leaves to go back to space.

Our livelihoods and economic activities take resources and energy from the Earth, create products and services and consume them, and in that process we ultimately return CO2 and other wastes to the Earth. That is the process. Seen from the perspective of our economy and livelihoods, the Earth is a both a source and a sink.

For our economic activities and life on the Earth to be sustainable, what is needed? Obviously, we must keep our extraction of resources within what the Earth can supply, and return waste to the Earth within the limits that the Earth can absorb. Since the Earth is finite, there are limits to what the Earth can supply and absorb. The amount that the Earth can sustain is known as "carrying capacity." In other words, the only way to achieve a sustainable society is to keep our economic activities and livelihoods within the carrying capacity of the Earth.

Limits to growth

But since humans appeared on the scene, nature and the Earth were so much larger than us humans, and whatever we did, it was difficult to imagine having any impact on the Earth. As if no limits existed, humans have gotten into the habit of extracting a lot of things from the Earth and disposing a lot of things back to the Earth. And the powers of science and technology have dramatically expanded what humans are able to do.

As a result, today, the ecological footprint is 1.6 Earths. In other words, if we convert to area the amount of agricultural land and forest, and so on, needed to sustain the current level of human activities, the Earth would not be able to sustain it. In fact we would need 1.6 Earths.

Image by johnhain.

The simulation of global warming you saw a minute ago is also a phenomenon that is occurring because we are exceeding the capacity of one Earth. The Earth's forests and oceans only have the capacity to absorb only so much CO2 in a year. If we release CO2 within that limit, global warming will not occur. But today we are emitting far more than the Earth can absorb, so the amount that cannot be absorbed is accumulating in the atmosphere, acting as a greenhouse gas.

These kinds of facts and knowledge have been stated before. We have heard of things like "Limits to Growth." As you know, a pioneering work in all of this was "Limits to Growth," released in 1972. It was the result of simulations done by Dennis Meadows and Donella Meadows -- great leaders in the academic world of system dynamics and sustainable development -- commissioned by the Club of Rome.

Have you heard of the IPAT equation?

I.P.A.T stands for Impact = Population X Affluence X Technology.

Take CO2 for example. Total CO2 emissions equal population times per

capita GDP times CO2 emissions per unit of GDP. Incidentally, both the

global human population and per capita GDP are increasing at a dramatic

pace.

The thinking until recently was, "Even if population or affluence increase, we can reduce environmental impacts with technology." In particular, the underlying ideology was that limiting an increase in affluence would have a large negative impact on the economy, but that it would be possible to limit the total impact by using technology, without affecting affluence. So innovation has been promoted. Energy saving and renewable energy technologies, for example. Technologies have been developed to reduce the CO2 emissions per unit of GDP (emissions intensity), and they are finding applications.

And thanks to the power of technology, it is true that CO2 emissions per unit of GDP are improving or going down. Since 1990, the CO2 intensity has improved by 0.7% annually. If you calculate the CO2 emissions per unit of GDP, 860 grams in 1990 declined to 760 grams in 2007. However, this improvement is not large enough to counter the effects of increases in population and affluence, so the "I" (impact, or CO2 emissions) continues to increase.

Tim Jackson of the University of Surrey in England calculated the amount of "T" (or CO2 emissions per unit of GDP) needed to suppress the increase in total emissions, if the GDP per capita continues to increase as it has before. According to that calculation, it has to be 40 grams in 2050, or about 1/20th of the amount in 2007. Is that even possible?

And if we assume that economic growth will not stop in 2050, it means that it has to decline even more after that. And it will eventually be necessary for CO2 emissions per unit of GDP to go from zero to negative. In other words, the more GDP increases, the more CO2 in the atmosphere would decrease. No matter how much faith you put in technological innovation, is that really possible?

If you think about what I just said, even as innovation advances, we really have to reconsider the topic of "affluence," which has not been seriously discussed until now. How high does the GDP per capita have to increase? In other words, should economic growth really continue forever? But no... Since we are already hitting the Earth's limits now, don't we have to shift to a steady-state economy? Is there a point after which the economy should not always continue expanding?

An important thing to consider is that affluence or wealth should not be measured using per capita GDP. It should be measured in terms of well-being, or happiness. In other words, I think we must pursue "well-being within limits."

Steady-state Economics

I once spoke with an official from Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) about the need for a steady state economy. He said, "The economy is like a bicycle. It moves because you continue pedaling. If you stop pedaling you will tip over." But in my opinion, that is not correct. To keep the economy moving on the same scale as the year before -- or in the case of a bicycle, to continue moving forward at the same speed -- that is a steady-state economy. But if we are talking about today's economic growth -- always growing bigger than last year -- that is like making the bicycle continue accelerating. And which of these ideas is really the sustainable one?

In a steady-state economy, the size of the economy -- or more precisely, the throughput of economic activity -- is constant. And this is NOT a dead economy. There is dynamic economic activity going around, new companies can be created, and companies can also become obsolete. Some new products can be created, and just like today, popular trends can be born. But the key point is that the material throughput itself stays within the carrying capacity of the Earth.

Do you think it is impossible to imagine the condition of an economy that doesn't have economic growth? Do you think the people in such an economy would have to be unhappy? Actually, in the past, Japan experienced an era in which it maintained a steady-state economy. For 250 years. So now, let's have a look at Japan's Edo or Tokugawa period.

Edo Period -- Japan's Sustainable Society in the Edo Period (1603 - 1867)

For approximately 250 years during the Edo Period, Japan was self-sufficient in all resources, since nothing could be imported from overseas due to the national policy of isolation.

http://www.japanfs.org/en/news/archives/news_id027757.html

Economy of the Edo Period

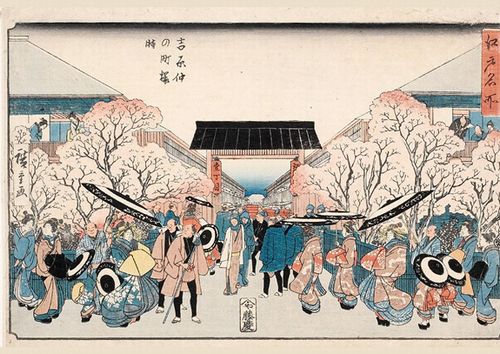

During the Edo Period, the word used to mean "economy" was four written characters pronounced "keisei saimin", which means something like "govern the country" and "save the people." The purpose of the economy was not to increase the GDP numbers but to ensure that all the people were saved or cared for. Experts on the Edo Period tell us that this was a time that material things were circulated and put to the greatest possible use within a paradigm of finiteness, and people were appreciated or valued for their ability to make the most of things.

Image by Utagawa Hiroshige.

The famed Omi merchants were based in the Omi region (today's Shiga Prefecture) and conducted business widely in Japan from the Edo to the Meiji Period (the 1600s to the 1800s). They had a guiding principle "sampou-yoshi", which means that things would be good if three players were happy: the buyers, the vendors, and society.

Rather than seeking only their own profit, they tried to offer products that would make many people happy. And if they accumulated enough profits, would pay to build bridges and schools for free, making significant contributions to society. That is how they gradually built up the trust of the people. These days, there is much talk about corporate social responsibility, but their "sampou-yoshi" then was a management philosophy like today's CSR, with the idea that business is not just for our own profit, but obviously it must also benefit the customers who buy from us, and society as a whole.

Meanwhile, the merchant families of the Edo Period had tradition in which the head of the household would "retire" at about age 40 or 50. In today's thinking, it would mean leaving the day-to-day operations and becoming the chairperson of the company. When one became the "chairperson," one would study Buddhist teachings, and examine the right way of running the business, things he may not have understood during his active business years, think about how life should be lived, study how people should have a perspective of something greater than the individual, and convey these teachings to the company president and employees who were still actively working.

Then the president and employees would learn the lessons of Buddhism from the chairperson, and apply them to the business. That is said to have been a system in which management was not focused only on short-term profits, but on conducting business sustainably.

By the way, do you know where the world's oldest company is? In Japan. It is Kongo Gumi, an Osaka construction company established in AD 578. It was started over 1,400 years ago, and to this day it still builds temples and shrines. Besides that company, a Japanese inn in the Hokuriku region was founded nearly 1,300 years ago, a Kyoto confectionary maker is more than 1,200 years old, a Buddhist objects maker, also in Kyoto, is over 1,100 years old, and there is a pharmacy/medicines business well over 1,000 years old.

University researchers estimate that Japan has more than 100,000 companies that were founded more than 100 years ago. Incidentally, there is an international organization based in Europe named the Henokiens Association, which only accepts into its membership family-owned companies that have a history of at least 200 years. The oldest European member was established in 1,369, but there are almost 100 companies older than that in Japan . If a company is only seeking to expand profits in the short term, it would probably not be possible to maintain continuous operations this long.

Images from the Past

What were conditions like for ordinary people during the Edo Period? I will read some excerpts from notes and letters written by Westerners who visited Japan between the end of the Edo Period and the beginning of the Meiji Period.

"How optimistic and kind-hearted are the people of Japan! What a satisfied and tidy people they appear to be!"

"One cannot find a happier people. They go about chatting and laughing. The men hum a tune while balancing the loads they carry. Whether they are far or near, they fill the air with lovely greetings of 'hello, hello,' and 'good bye, good bye.' In the evening, they say 'good night.' The deep bows exchanged in the streets by these diminutive people are charming and are an open display of elegance and good will. Even the rickshaw driver, when he meets an acquaintance or when negotiating to pick up a customer, bows politely like a first-class teacher of etiquette."

"That the residents do not lock their doors and make no effort to prevent crime, and have no concern about leaving the home unattended all day long, speaks clearly of their honesty." "I would leave all of my things, even small change, without locking anything, and not once did anything go missing."

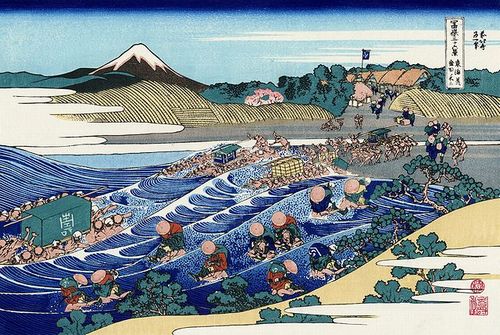

Mary Crawford Fraser, the wife of British diplomat Hugh Fraser, writes this description, having observed net fishing at a beach in Kamakura, in 1890.

"It is a beautiful scene...brown men wrapped in blue cotton cloth around the waist, standing in the sea, extending the net which contains a dancing multitude of silver fish. In the background is the sea with the setting sun, and in foreground, a velvet sandy beach. Then it is time for children to collect the catch. And it is not only children, but also widows who are unable provide any men for fishing, or elderly who have lost their sons, they gather around the fishermen and hold out their pots and baskets to receive something. Whatever fish are not good enough to sell at the market goes to the hands of these people. ... It is nice to see that not a nasty word is spoken to the beggars. And the beggars may be as poor as the grey weeds on the beach, but they have no appearance of despair, filth, or misfortune."

Image by Katsushika Hokusai.

Current Initiative in Japan

Now let me sift our attention to today's Japan. In Japan, like in other countries, many people believe that economic growth is essential for the country as a whole.

But we can find examples where people have come to their own realization of the need for a steady-state economy, and who have made a shift toward a steady-state economy.

Sakura Shrimp Farming

Copyright Yui Fisherman's Association

All Rights Reserved.

The example of sustainable fisheries initiatives is in Suruga Bay, which is graced with views of the iconic Mt. Fuji, where three fisherman's associations of Yui, Kambara, and Oigawa towns harvest sakura shrimp (spotted shrimp). The fishing by the three associations is one of the largest coastal fisheries in the prefecture, earning four billion yen (about U.S.$35.4 million) annually. Sakura shrimp grow to four or five centimeters long and are a kind of zooplankton that lives only for one year.

Its peak spawning period is from June to August. Sakura shrimp fishing was once conducted all year round in the bay, but now it is limited to two fishing seasons-one in spring (late March to early June) and one in the fall (late October to late December), under the fishery management rules set by Shizuoka Prefecture and voluntary agreements by the local fishermen.

This fishery management started in response to the large drop in catches of the shrimp by several hundred tons between 1964 and 1965. At the time, Suruga Bay was polluted with wastewater from paper mills and a great amount of sludge that had accumulated in Tagonoura Port. Facing the resource and pollution problems, the fishermen realized a serious threat, that their shrimp fishery would collapse in the near further if they continued fishing.

In 1966, the Yui district first started a new fishery operation on a trial basis. It is called a "pooling system," based on equal allocation of the gross sales. After that, the Kambara and Oigawa districts also implemented the system. But then the three districts had a severe competition with each other over the shrimp harvest, as they shared the same fishing area. Their rivalry became more intense and threatened the effectiveness of their management of resources.

During the spawning period in summer, fishermen themselves take sample sea water in the district and look at it with microscope in order to count eggs of shrimp. Twice a week they count and their record is sent to the fishing department of the Prefecture. With the data, they can decide how much they can harvest without destroying the reproduction base of the shrimp.

Meanwhile, sludge pollution in Tagonoura Port became a serious problem for the community, so the fishermen mobilized together against the pollution. A strong solidarity was formed among them, beyond the differences of the districts, and they gained momentum to address their common problems cooperatively. As a result, a consolidated pooling system was adapted in 1977 to manage all 120 fishing boats in the three districts. Allowing all the boats under the three associations to operate, the new system was thus established to distribute the sales from the shrimp fishing evenly to each boat.

Every day around noon during the shrimp fishing season, a fishing control committee, consisting of members from the three associations, discusses the fishing details of the day, such as the availability of the fishing operations, catch quota of the shrimp, fishing site, and departure time. The committee designates a flagship boat of the day, in advance. When all the boats arrive at the site, the leader boat sends a message over the radio and they start fishing. After harvesting, boats that hauled their trawl net report each yield to the leader by radio. When the total yields that the leader sums up reach the quota set by the committee, the operation of the day is to be completed.

All boats then return to each association's facilities to land the day's catches of shrimp. After deducting a sales commission from the total earnings, the rest is divided into two parts: 53 percent for boat owners and 47 percent for the fishermen crew members. Each portion is distributed equally based on the number of the members respectively.

Mochizuki, an executive board of the Yui Fisherman's Association, says, "The sakura shrimp lives only for one year. Catching mature shrimp disrupts spawning, which would mean we couldn't harvest the offspring either. The shrimp resource in our fishing areas resembles the principal in a bank. We can live on the interest without spending the principal." Spending the principal because of temporary low fish prices or greed would lead to future collapse.

Marine resource management is often seen as a challenging task because the resources are difficult to measure and therefore it is impossible to know for certain how much of the "principal" is left, or even its trend of increase or decrease. In the case of the sakura shrimp fishery, a spawning survey is conducted every two days during the fishing off-season every summer, by checking seawater temperature, and the conditions of egg production and development. Calculating the number of eggs per cubic meter is one rough indicator of fluctuations in marine resources. The system introduced here is to share equally the profits from fishing, by setting the feasible catch of the year, and fishing according to the quota during the fishing season.

Mochizuki emphasizes that "without this pooling system, our fishery would not be sustained. We would have caught all the resources within two to three years." Fisheries like this example, with marine resource management by a comprehensive pooling system, is rarely seen in Japan or other countries. The sakura shrimp fishery in Suruga Bay, which created such a system almost 40 years ago and kept its rules up to the present, offers some insight and hope for production systems in a sustainable society.

Image by 4510waza Some Rights Reserved.

'Naimono-wa-nai' ('What we haven't got we do without')

This is another interesting movement in Japan.

Ama Town in Shimane Prefecture is three hours by ship away from the mainland. It has a population of 2,370, and the town's island is very small as it takes only one and a half hours to drive around it. The town's annual budget is four to five billion yen (about 39 to 49 million US dollars), and it has one nursery school, two elementary schools, one junior high school, and one high school.

Ama Town is one of the most depopulated townships in Japan and faces all the problems of a super-aging society. Ama's current aging rate is equivalent to what the national average is projected to be 50 years from now. In fiscal 2005, the town mayor initiated a new start by drastically reducing town hall salaries to the nation's lowest level as compared to the standard of other municipalities. This involved a 50 percent cut for the mayor and 16 to 30 percent cut for town officials.

At the same time, he adopted two aggressive strategies; developing products by branding the whole island, and offering one of the nation's highest quality education programs as a full-fledged effort of the entire town. And now these efforts are bearing fruit - attracting young people to the town. Oki-Dozen High School, the only high school in the Dozen region, was experiencing a decline in its number of students. When enrollment dropped to 28 in 2008, the high school feared that it would be forced to close by 2014. Two measures to reverse the situation were tried; one aimed to encourage students in the area to go to this high school, and the other aimed to increase the number of students coming in from outside (including overseas countries) through an exchange program. They saw a V-shaped recovery in the number of prospective students.

Pursuing Local Economy and Well-Being in Ama Town, Shimane Prefecture

http://www.japanfs.org/en/news/archives/news_id034869.html

The slogan of the town is "Naimono-wa-nai" (What we haven't got we do without). It was created by the a group of younger staff from the town office, and has two meanings: the town does not need to have what the town does not have, while it does have everything that is important.

Ama Town on the remote island is not as convenient as the big city, and it does not have material abundance. On the other hand, it is blessed in natural and local features. They have enough of what they need to live, and are making good use of the things that they have. The saying "What we haven't got we do without" was chosen to symbolize Ama Town and express boldly the appeal and uniqueness of island life.

Isn't true happiness all about cherishing the connections with people in your community, not wanting wasteful things, and living a simple but full life of sufficiency? What is true wealth? Japanese values have been changing significantly since the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, but the happiness that allows people to sincerely declare "What we haven't got we do without" is already there, in Ama Town.

Today I am working with others to promote an initiative to create an indicator for the idea of "What we haven't got we do without." Behind the idea of "What we haven't got we do without" is the context of a sense of values of knowing sufficiency-"We have everything that we need," the confidence that we can obtain what we really need (water, food, and so on), and that we do have the social capital to sustain daily life and happiness. At the same time, an important point is the idea in daily life of "making do without what you don't have," a spirit to take on the challenge of "making whatever we need," and the presence of a community of members who will support each other in that challenge.

It is about not despairing about not having something. The initiatives of Ama Town are about wanting to be an island community that can say, with confidence, "What we haven't got we do without." They are different from today's predominant sense of values of "we have to have material growth forever." And all of that has a connection to sustainable society.

Image by GanMed64 Some Rights Reserved.

Asia's Wisdom for the World

I shared two examples for steady-state economy from Japan, one is old one and another is current one. These ideas and approaches toward "well-being within limits" are found not only in Japan but also in many other places in Asia and the East.

In 1972, Bhutan's fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, started to say that "GNH, gross national happiness, is more important than GNP, gross national products." And Article 9 of Bhutan's Constitution-promulgated in 2008-declares that, "The State shall strive to promote those conditions that will enable the pursuit of Gross National Happiness." This is based on the idea that sustainable development requires a wholistic approach, and that besides the economic perspective, happiness (or well-being, or good life) needs equal attention.

Bhutan has identified indicators of Gross National Happiness, based on nine "dimensions," and is using them to evaluate its policies. The nine dimensions are psychological well-being, living standards, good governance, health, education, community vitality, cultural diversity and resilience, time use, and ecological diversity and resilience.

Also Thailand has promoted the idea of "sufficiency economy" as its approach to development.

These approaches and ideas have become known to the rest of the world in bits and pieces, and I think that they are something that Asia can still offer as a significant contribution to the world as the world searches for sustainable society. I would really like to spread these ideas more proactively.

These approaches and ideas have become known to the rest of the world in bits and pieces, and I think that they are something that Asia can still offer as a significant contribution to the world as the world searches for sustainable society. I would really like to spread these ideas more proactively.

I believe that one of the roots of this Eastern and Asian thinking is Buddhism. Buddha said that "All life is suffering."

In India's ancient Sanskrit, "suffering" has the meaning of "not going as you wish," and it expresses the idea that "If you think in such a way as to want things more your way, the desire gets bigger and stronger, and you end up with things even more not going as you wish." "If you are attached to that desire, eventually, you will be controlled by that desire." Buddha's response to the condition of desire is that you should avoid being ruled by desire. If you are not ruled by desire, you enter a state of freedom from desire, and this is an ideal state in Buddhist thought, known as Nirvana.

This is sometimes expressed in a figure like this:

Happiness is how much you have divided by how much you want.

If you want to increase happiness, the typical Western-style approach would probably be to increase "what you have" (or possessions). Work harder. Increase your income. And then increase what you have.

But what about the Eastern style or Buddhist approach? Rather than increasing your possessions, you would increase happiness by reducing desire. At the core is a value system expressed with the characters "sho-yoku-chi-soku" which could be translated as "small / desire / learn / sufficiency" or "I will know sufficiency if I have small desire."

There is a famous temple named Ryoan-ji in historic Kyoto, visited by many Japanese people. A ritual washbasin at its entrance is deep with meaning. Four characters are engraved on the stone, centering on the square-shaped character for "mouth." They are "I", "only", "plenty", "know"(*). This could be translated as "what one has is all one needs." Or "learn only to be content." Or "I only know that I have enough."

Ritual washbasin.

CONCLUSION

The challenges of sustainability, including climate change, are the "grand issues" of our generation. How will we tackle them? Can we offer or contribute to solutions? Whether we are talking about the specific field of sustainable development, or about other academic fields and disciplines, those are key questions.

This is Herman Daly's pyramid model. As I mentioned earlier, we obtain raw materials from the Earth, create products and services, and consume them. But the ultimate goal is not things like smartphones and cars, but the happiness that they are supposed to create.

However, in our economy and society today, we turn our attention to efficiency in a narrow sense: "How much product did we create from how much raw material." But we should think not about that, but at the big picture of the invisible linkages, fundamental sustainability, and comprehensive efficiency of providing happiness, which is the ultimate objective of extracting raw materials from the Earth. Also, how everyone can be happy.

Using simulation models, sustainable development can show us the possibility or potential to make the linkages visible, to show where we should really put our efforts. I have high hopes and expectations for this.

Also, the twelve leverage points identified by Donella Meadows to change the system are very useful. It is difficult to change the values I mentioned earlier, but these are big intervention points for leverage.

In that sense, I believe we need to think about this as Asians and transmit from Asia to the world the thinking of "taru wo shiru" (sufficiency), well-being within limits, and that that is what leads to sustainable happiness.

Thank you.

Junko Edahiro